Bermuda & Cayman At Opposite Ends Of Fiscal Policy

At first glance, Bermuda and the Cayman Islands look similar in many ways: size, economic dependency on financial services and a low-tax regime.

Both have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and its related lockdown measures through a rise in healthcare-related costs and deteriorating government revenues.

But while Cayman has so far been able to rely on a cushion of more than CI$500 million in cash reserves, the situation is strikingly different in Bermuda.

Last week, Bermuda Finance Minister Curtis Dickinson outlined that the island’s total debt had increased by US$520 million to US$2.82 billion, as a result of the pandemic.

Bermuda, like Cayman, had allowed its residents to dip into their private pension savings with the withdrawal of a $12,000 lump sum. In addition, the government expanded unemployment benefits to more than 9,700 people for up to 16 weeks, racking up $38 million in costs by June alone.

The “very positive news”, Dickinson said, was that Bermuda’s government raised $1.35 billion in new bonds. All it took was a series of virtual meetings with some of the world’s top investors to generate “healthy demand” in the bonds.

Bermuda’s government used a portion of the raised funds to pay down its on-island credit line and $500 million in existing bonds to lower its interest costs. Bermuda will pay 2.375% on the 10-year bond and 3.375% on the 30-year bond, each representing half of the total amount raised.

According to Dickinson, the average interest on the government’s debt portfolio dropped by 0.59%, even though much of the bond issue represents new debt.

To facilitate the bond issues, in July Bermudian legislators had to raise the country’s debt ceiling by $600 million to $3.5 billion. When Dickinson’s Progressive Labour Party government took over after the 2017 election, the total net debt stood at $2.4 billion.

Years of surpluses end in 2020

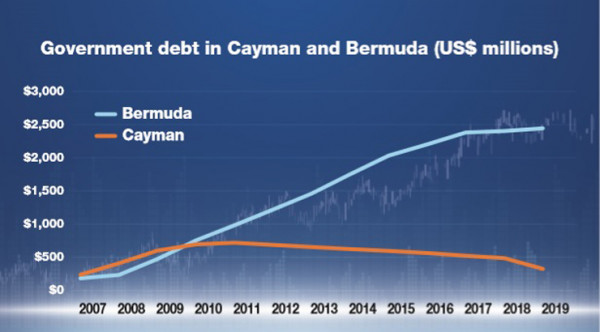

These are eye-watering figures compared to Cayman’s fiscal situation. Cayman’s government prides itself on having turned around government finances following the 2008 global financial crisis. As of 30 June, Cayman had about CI$266.5 million in public debt.

After seven years of budget surpluses, Cayman Islands Finance Minister Roy McTaggart is projecting for this year an operating deficit of CI$173.2 million, rather than the initially budgeted surplus of CI$65.3 million.

So far, government could rely on its higher-than-expected cash balance of $559.6 million, as of June 2020, to cover revenue shortfalls and COVID-19-related costs and economic-stimulus measures.

To avoid a depletion of Cayman’s cash reserves and to help meet financial obligations over the next two years, the government is currently seeking a loan of CI$500 million (US$609.7 million) from a syndicate of local banks.

Asked at the recent Chamber Economic Forum why Cayman was not tapping the liquid bond markets to raise the funds, thereby taking advantage of low interest rates and Cayman’s very high credit rating, McTaggart said its request for proposals had invited all kinds of bids.

However, government had previously indicated that it preferred an offer from local banks.

Another reason for choosing a loan facility over a bond issue is that government does not intend to draw down the funds immediately, but only if needed, in order to reduce interest costs.

It currently projects that drawing down a portion of the loan will increase debt balances to CI$273.6 million by the end of 2020.

This would still be many multiples less than Bermuda’s debt, which is expected to exceed $3 billion this year.

Fiscal strength

However, despite these significant differences, neither Cayman nor Bermuda are believed to be carrying unsustainable debt levels.

Economist Marla Dukharan noted in a presentation in May on the impact of COVID-19 that the balance sheet strength of both British Overseas Territories means they are well prepared and insulated to weather this storm compared with other countries in the region.

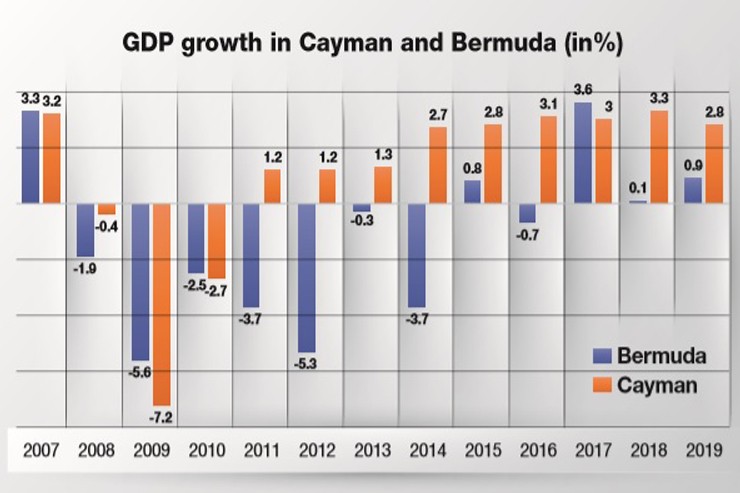

Cayman is one of the least-indebted countries in the Caribbean. Because Cayman’s government debt level is below 10% of GDP and it has recorded seven consecutive years of fiscal surpluses on the back of positive and stable growth since 2011, the islands are “a tremendous outlier”, even globally, she said. The combination of austerity, or fiscal prudence, and growth is not seen often but they can go hand in hand, Dukharan noted.

This is recognised by the rating agencies. Cayman has maintained a high Aa3 rating with a stable outlook from Moody’s since December 1997.

Although Bermuda has seen constantly rising debt levels for the past 14 years and growth has been patchy, its credit rating has declined only marginally from AA stable in 2010 to A+ stable in 2020.

This year, Standard & Poors revised the outlook of the rating from positive to stable but decided against a downgrade. The lack of a downgrade was crucial for the bond issues that followed. A lower debt rating would have caused bond investors to demand higher interest rates and raised the debt-servicing costs.

As it stands, investors and rating agencies are not overly concerned about Bermuda’s debt levels at more than 30% of GDP.

Moody’s, for instance, found in its latest assessment that Bermuda’s fiscal strength, one of the key factors to determine the credit rating, was high, and reflected “its fiscal reserves and relatively low and stable debt burden compared to its peers”.

When Moody’s measures fiscal strength, it mainly looks at debt burden and debt affordability. It essentially combines four metrics – debt-to-GDP, debt-to-revenue, interest payments-to-revenue, and interest payments-to-GDP – to arrive at a fiscal strength score.

The assessment shows just how much leeway Cayman’s government would have to raise additional debt if the economic crisis lasts several years.

Financial management

However, the currently low debt level is caused as much by government’s fiscal conservatism and good fortune, in the form of consistently strong economic growth in recent years, as it is by design.

The Public Management and Finance Law sets clear parameters for how much the government can borrow.

It mandates that Cayman should generate an operating surplus and net debt should be no higher than 80% of central government’s revenue, while debt servicing must be below 10% of revenue. In addition, government should have enough cash to cover 90 days of its expenses, and its net worth, currently $1.4 billion, should be positive.

These benchmarks were agreed with the UK government in 2011, after the motherland feared it could be ultimately on the hook for Cayman’s rising debt at the time.

Although the net debt and debt-servicing ratio are estimated to remain well within these parameters, government is forecasting an operating deficit and believes it will deplete its cash reserves to 47 days of operating expenditures.

As a result of the breach, the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office will have to approve any new borrowing or the refinancing of existing debt, any sale of public assets or their use as collateral, as well as any project with a lifetime value of more than CI$10 million.

SOURCE: Cayman Compass by Michael Klein, August 28, 2020